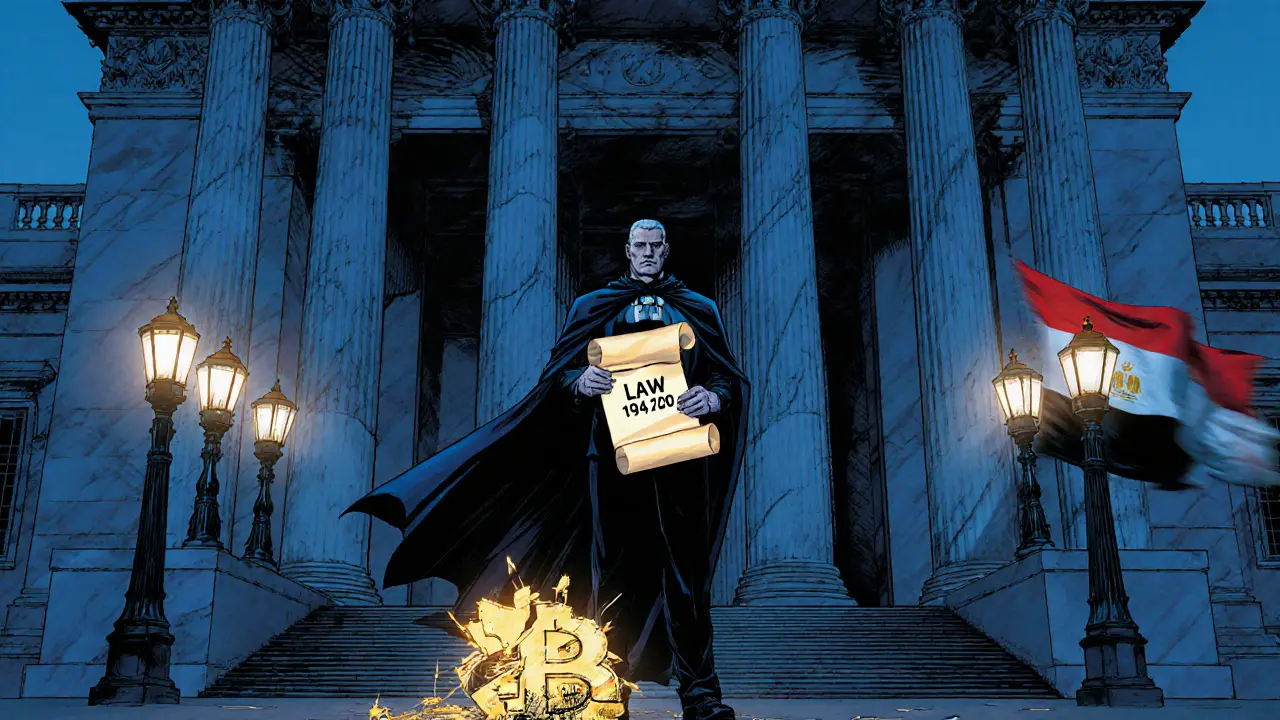

Egypt has one of the toughest stances on digital money in the Middle East. Since 2020 the Central Bank of Egypt (Central Bank of Egypt), or CBE, has slapped a blanket ban on any crypto activity that isn’t cleared by the regulator. The rule lives inside Law No. 194/2020, which was originally meant to shape the whole banking system but now doubles as a crypto blacklist. If you’re wondering why the ban exists, how it’s enforced, and whether any part of the technology is still allowed, keep reading - the answer is a mix of legal firepower, religious guidance, and a cautious embrace of blockchain for non‑financial use cases.

What Law No. 194/2020 Actually Says

The law was passed in 2020 to formalize the CBE’s role in Egypt’s financial sector. Section 12 of the act explicitly forbids the issuance, trading, or promotion of cryptocurrency without prior approval. The phrasing is absolute: “any dealings with encrypted virtual currencies are prohibited.” That means exchanges, peer‑to‑peer trades, ICOs, and even advertising crypto services are illegal unless the CBE grants a special licence - and no such licence has ever been issued.

Why the CBE Took a Hard Line

Two big reasons drive the prohibition:

- Financial stability. The CBE worries that volatile crypto prices could destabilize the Egyptian pound and make monetary policy harder to manage.

- Consumer protection. A 2020 warning letter warned that most crypto projects are scams, with no recourse for Egyptian investors.

Adding a religious dimension, a 2018 Islamic fatwa declared digital assets haram, reinforcing the legal ban with a moral argument. The dual pressure makes it clear the government wants to keep crypto out of the mainstream.

How the Ban Is Policed - The Reality on the Ground

In theory the CBE monitors banks, payment processors, and licensed financial institutions for any crypto‑related activity. In practice, enforcement is a mixed bag:

- Bank surveillance. Banks must flag any transaction that looks like a crypto purchase and report it to the CBE.

- Public warnings. The CBE releases quarterly statements reminding the public of the risks and the legal consequences.

- Legal actions. Few documented cases exist, but occasional arrests of individuals running small “over‑the‑counter” Bitcoin sales have been reported.

- International reports. The U.S. State Department noted in its 2025 Egypt Investment Climate Statement that enforcement is uneven, with some underground activity persisting despite the ban.

Because crypto transactions are peer‑to‑peer and can be routed through foreign exchanges, the CBE faces a technical hurdle. Monitoring tools are improving, but the decentralized nature of blockchain still creates gaps.

Crypto Still Exists Underground - What That Means for Users

If you’re an Egyptian citizen, here’s what the underground scene looks like:

- Friends or family members may trade Bitcoin or USDT via mobile messengers.

- Some small “exchange” sites operate overseas but accept Egyptian pounds through informal channels.

- Remittance services sometimes employ stablecoins to lower fees, skirting the ban at the edge of the law.

While the risk of a fine or imprisonment is real, most enforcement actions target large‑scale operators rather than casual traders. Still, the CBE’s stance makes any crypto activity a legal gray area, and the safest route is to avoid it altogether.

Blockchain Is Not Banned - Egypt’s Selective Adoption

Interestingly, the prohibition does not extend to the underlying technology. The CBE and other ministries have rolled out blockchain pilots for non‑financial purposes:

- Advanced Cargo Information (ACI) system. Customs uses blockchain to track shipments, cut fraud, and speed clearance.

- Land registration. Draft projects aim to store title deeds on a distributed ledger, reducing disputes.

- Supply‑chain tracking. Logistics firms experiment with blockchain tags to verify product origins.

This selective approach shows the government can see value in the tech while keeping the speculative crypto market shut.

What About a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)?

Even as crypto is outlawed, the CBE is exploring its own digital money. A Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) could give the state the benefits of fast digital payments without the volatility of private tokens. Pilot programs focus on cross‑border remittances, a huge market for Egyptians receiving money from abroad.

Key differences between a CBDC and a crypto token:

- Issued and fully backed by the central bank.

- Subject to the same regulations as cash.

- Fully traceable, which satisfies the CBE’s anti‑money‑laundering goals.

In short, a state‑run digital currency is acceptable, while decentralized crypto remains illegal.

Comparison: Crypto Ban vs. Blockchain Adoption

| Aspect | Cryptocurrency (Ban) | Blockchain (Allowed) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal status | Prohibited under Law No. 194/2020 | Permitted for non‑financial use cases |

| Regulatory focus | Consumer protection, monetary stability | Transparency, fraud reduction |

| Enforcement | Bank monitoring, occasional arrests | Government‑led pilots, no penalties |

| Religious view | Declared haram by 2018 fatwa | Technology seen as neutral |

| Future outlook | Ban expected to stay | Expansion in customs, land, logistics |

Practical Takeaways for Different Readers

Investors: Avoid Egyptian crypto exchanges. Look for offshore platforms if you must trade, but be aware of legal risk.

Businesses: You can integrate blockchain for supply‑chain, customs, or identity solutions without breaching the law. Any payment‑related use must stay within the CBE’s approved channels.

Policymakers: Egypt’s model shows you can separate the tech from the asset. Consider a CBDC if you want digital payments without the uncertainty of private tokens.

General public: The CBE’s warnings are real. Crypto scams are common, and the law can penalize even casual involvement. Stick to official digital services.

What Might Change?

The ban is unlikely to lift soon, but a few factors could shift the landscape:

- International pressure. Neighboring Gulf states are loosening rules, and global financial bodies push for clearer crypto policies.

- Technological advances. Better monitoring tools could make enforcement tighter, discouraging underground trade.

- Success of CBDC pilots. If a state‑run digital currency proves useful, the government might revisit the outright ban on private tokens.

Until then, the safest play is to respect the prohibition, keep an eye on official CBE statements, and watch for blockchain pilots that could open new business opportunities.

Is owning Bitcoin illegal in Egypt?

Yes. Under Law No. 194/2020, any ownership, trading, or promotion of Bitcoin without CBE approval is prohibited and can lead to legal penalties.

Can Egyptian companies use blockchain for supply‑chain management?

They can. The government encourages blockchain projects that improve transparency and reduce fraud, as long as no cryptocurrency is involved.

What penalties does the CBE impose for crypto violations?

Penalties can include heavy fines, suspension of banking licenses, and criminal prosecution that may result in imprisonment, though most public cases target large operators.

Is there any official Egyptian crypto exchange?

No. The CBE has not granted any licence to operate a crypto exchange within Egypt.

Will a Central Bank Digital Currency replace the crypto ban?

A CBDC would be state‑controlled and fully regulated, so it does not conflict with the ban on private cryptocurrencies. The ban is likely to stay while the CBDC is tested.

mike ballard

October 22, 2025 AT 02:25Egypt’s crypto clampdown is a textbook case of regulatory overreach 🚀. The CBE is basically saying “nope” to every token that isn’t handed a golden ticket, which in practice never happens. It’s a classic risk‑averse move, leveraging AML/KYC protocols and a dash of religious rhetoric to cement the narrative. The ban leverages Law No. 194/2020, a piece of legislation originally meant for banking reform but now moonlighting as a crypto blacklist. From a compliance perspective, this creates a high‑cost barrier to entry for any fintech startup dreaming of a tokenized future in Cairo. Not to mention the chilling effect on innovation pipelines that could have piggy‑backed on blockchain’s immutable ledger. The enforcement arm is multi‑pronged: bank surveillance, public warnings, and occasional crackdowns on underground “OTC” trades. While the law is clear, the enforcement is patchy-some operations slip through the cracks via messengers and offshore exchanges. Bottom line: if you’re looking to dip your toes in crypto while in Egypt, you’re swimming in regulatory quicksand.

Molly van der Schee

October 27, 2025 AT 22:53It’s really sad to see how many people get caught up in risky schemes because the official channels are closed. The ban, while meant to protect, often pushes folks toward unregulated circles where scams thrive. I feel for anyone trying to support family back home and ends up stuck. Still, the government’s focus on blockchain for logistics shows they see value in the tech itself.

john price

November 2, 2025 AT 20:21What the hell, man? This “regulatory overreach” you talk about is just the CBE playing god with every damn token. They can’t even spell “blockchain” right in their own documents, let alone manage a simple BTC transfer. If they’re so scared, why not just legalize and tax? Stop being a crypto‑phobic bureaucrat and let the market sort itself out.

Ty Hoffer Houston

November 8, 2025 AT 17:50The CBE’s approach is a mixed bag. On one hand, they’re guarding monetary stability, which is crucial for a country battling inflation. On the other, they’re stifling a sector that could bring financial inclusion. The blockchain pilots in customs and land registration are promising, showing that the tech isn’t the enemy-just the speculative tokens.

Ryan Steck

November 14, 2025 AT 15:18Yo, they’re not just “guarding stability”. This is a top‑down agenda to keep the power in the hands of the state. All those “pilots” are just PR stunts while the real crypto community gets demonized. They’ll blame “foreign influence” whenever a BTC trade pops up, but it’s all a controlled narrative.

James Williams, III

November 20, 2025 AT 12:47From a compliance standpoint, the key takeaway is that banks must implement transaction monitoring systems capable of flagging crypto‑related signatures. This includes pattern detection for known exchange wallets, AML alerts for high‑velocity transfers, and integration with the CBE’s reporting APIs. Without these layers, institutions risk hefty fines or license suspension.

Amy Kember

November 26, 2025 AT 10:15Legal grey area but still risky. No licence, no safety net. Even small peer‑to‑peer deals can draw attention if a pattern emerges. Stay low, use encrypted chats, avoid large sums.

Anna Kammerer

December 2, 2025 AT 07:43Oh great, another “ban” that people pretend to respect while secretly trading on WhatsApp. It’s like telling kids not to eat candy and then hiding chocolate bars in the pantry. The irony isn’t lost on anyone.

Mike GLENN

December 8, 2025 AT 05:12The landscape described in the article paints a picture of a governmental apparatus that is simultaneously progressive and restrictive, a paradox that can be traced back to the core objectives of the Central Bank of Egypt. On the one hand, the CBE’s emphasis on financial stability is understandable, given the country’s historical struggles with currency volatility and inflationary pressures. By enshrining a blanket prohibition against crypto assets in Law No. 194/2020, the regulators aim to eliminate a potential source of destabilizing capital flows, which could otherwise exacerbate the already fragile monetary environment. On the other hand, this same regulatory framework stifles the entrepreneurial spirit that could harness blockchain’s immutable ledger for public‑good applications, such as supply‑chain transparency and land registration, as highlighted by the ongoing pilots. The duality becomes even more striking when you consider the religious fatwa that brands digital assets as haram, adding a moral dimension to a primarily economic policy. While the enforcement mechanisms-bank surveillance, public warnings, and occasional arrests-signal a serious intent, they also reveal practical limitations, especially when transactions are routed through overseas exchanges or encrypted messenger platforms. The underground ecosystem, though small, adapts by leveraging stablecoins for remittances, effectively skirting the law while still providing the desired financial service. This cat‑and‑mouse game underscores the importance of a nuanced approach: outright bans might drive activity into the shadows, whereas calibrated regulation could channel innovation into approved channels. Moreover, the government’s willingness to experiment with blockchain in customs and land registries suggests an appetite for the technology’s benefits, provided it remains under state control. The exploration of a Central Bank Digital Currency further illustrates a strategic compromise-offering digital payments without relinquishing oversight. In practice, however, the success of such initiatives will hinge on public trust, technological robustness, and the ability to integrate seamlessly with existing financial infrastructure. For the average Egyptian, the safest path remains to avoid crypto altogether, but the allure of higher yields and low‑cost remittances will continue to drive clandestine participation. Ultimately, the policy equilibrium will depend on how effectively the CBE can balance its protectionist instincts with the global momentum toward digital finance, and whether international pressure can nudge a more flexible legal environment.

BRIAN NDUNG'U

December 14, 2025 AT 02:40Esteemed colleagues, it is incumbent upon us to recognize that the Central Bank's regulatory posture, while seemingly austere, is rooted in a fiduciary duty to preserve macro‑economic equilibrium. The prohibition, therefore, must be construed not merely as a punitive measure but as a preemptive safeguard against systemic risk. I remain optimistic that future dialogues will yield a calibrated framework that accommodates both stability and innovation.

Donnie Bolena

December 20, 2025 AT 00:09Wow, what an exciting development!!, the CBE is really leading the way, protecting us from volatile crypto chaos, and at the same time exploring blockchain for customs, land titles, and supply chains, which is absolutely brilliant, this dual strategy shows they care about both security and progress, let’s hope they keep it up, and maybe one day we’ll see a CBDC that finally resolves all these issues!!

Elizabeth Chatwood

December 25, 2025 AT 21:37the ban is real and the penalties are heavy but the blockchain pilots are cool and can help the economy

Tom Grimes

December 31, 2025 AT 19:06I think the ban is a classic case of fear of the unknown. The government sees crypto as a threat because it cannot control it, so they clamp down hard. Yet they love the underlying tech, using it for customs and land registries. This split personality shows they understand the tech’s value but not the asset. People still find ways to trade, often through messengers or overseas platforms, because demand doesn’t disappear. The risk is that underground markets become breeding grounds for scams. If the state wants to protect its citizens, it should consider a licensing regime instead of an outright ban. That would bring activity into the light, allow for better monitoring, and maybe even generate tax revenue. Until then, the cat‑and‑mouse game will continue, with users constantly adapting to evade detection.

Paul Barnes

January 6, 2026 AT 16:34Interesting that the ban stays while the CBDC gets tested – classic double‑standard.

John Lee

January 12, 2026 AT 14:02Imagine a world where Egypt’s high‑tech blockchain pilots skyrocket, creating jobs, while crypto stays in the shadows. It’s a colorful paradox that could inspire a new wave of innovators who respect the law but still dream big.

Jireh Edemeka

January 18, 2026 AT 11:31Oh, the irony-calling something “haram” while the state pats itself on the back for “blockchain pilots.” It’s almost comedic how the narrative flips depending on who’s profiting.

Rebecca Kurz

January 24, 2026 AT 08:59Wow!!! This ban really scares off investors!!!

Nikhil Chakravarthi Darapu

January 30, 2026 AT 06:28As a proud citizen, I must say that protecting our national currency from such destabilizing forces is paramount. The Central Bank's firm stance ensures that foreign speculative assets do not undermine Egypt's economic sovereignty. Any attempt to loosen these restrictions would be an affront to our national interests.

Tiffany Amspacher

February 5, 2026 AT 03:56Well, look at that-another drama with a government playing the villain and the crypto community as the misunderstood hero. Spoiler: nobody wins.

Patrick Day

February 11, 2026 AT 01:25They’re hiding the truth, man. Every time they talk about “stability” they’re just covering up the fact that they can’t handle a real decentralized network. Wake up!